The Last Word: Sadruddin Aga Khan-2002-09

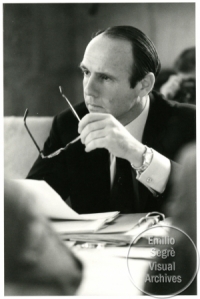

Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan doesn’t look much like a fire-breathing ecowarrior. With an Iranian passport, an American education, a Geneva address and a long career as a U.N. diplomat, he’s not the sort of man one expects to rage about man’s inhumanity, the spooky power of multinational corporations or the toothlessness of many U.N. institutions. But he does.

UNCLE OF THE CURRENT Aga Khan, who is hereditary imam, or spiritual leader, of the Muslim Ismaili sect, the prince is a former U.N. high commissioner for refugees, and continues to serve as special consultant to U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan. He spoke to NEWSWEEK’s Carla Power from the Geneva headquarters of his Bellerive Foundation, an environmental NGO, about globalization and his take on the Johannesburg summit.

You’ve spoken out recently against the concept of sustainable development. Why?

The term itself reminds me of Mahatma Gandhi’s response when someone asked him what he thought of Western civilization. He said, “I think it is a good idea.” Sustainable development could be a good idea, particularly when we take it in the context of the noble intent for which it was originally coined: that we should not take more from the Earth than we give back. It implies solidarity between current and future generations. But I object to the way the term has been diverted to become a meaningless buzzword. It’s become an alibi for human greed, for lifestyles that are anything but sustainable. “Sustainable” has taken on a different meaning: it now means what the market will bear, not the Earth.

What’s changed as the meaning of the term has changed?

It’s simply not working at any level, from conservation to alleviating climate change or global disparities. The ethical dimension is totally absent from the current thinking on sustainable development. For example, purse-seine fishing for tuna, which causes the cruel death of thousands of dolphins, may be technically sustainable, but it’s not ethical. This shouldn’t be written off as oversentiment for animals and nature. Even men and women are now referred to as “human resources.” The ethical, social, spiritual dimension is completely obliterated by the present sustainable-development mind-set.

You’ve spoken out for the need for legislation to protect against the dangers of misuse of natural resources by corporations.

I’m not against corporations, or business. The concept of self-regulation worries me: it’s a bit like leaving it to motorists to decide what constitutes speeding. It’s also a disincentive to abide by the spirit of the rules: the good guys realize the ones who violate them are making more money. So why shouldn’t they do the same?

How does the resistance to any sort of global accounting system actually work?

There’s an enormous resistance to having any kind of international corporate-accountability convention which can be legally enforceable, or a code of conduct that’s anything more than voluntary. It’s a pity, but it’s also bad corporate vision. Preserving nature can have immense economic benefits. The returns on investing in, for example, long-term forest conservation or ecotourism generally far outweigh any short-term gain to be derived from exploitative—so-called wise use—of wildlife and natural resources. Preserving a coral reef can bring more in terms of tourism than large-scale fishing in such fragile coastal zones. That said, it’s very difficult to put a price on these things, and that’s precisely one of the problems. By giving everything a price tag, and insisting that nature must “pay its way” to survive, we have lost sight of the intrinsic value of creation.

How seriously do you think governments are taking the Johannesburg summit?

Look at the power and status of the environment ministers and their trade counterparts. In Britain, [Environment Minister] Michael Meacher was, for a time, removed from the Johannesburg delegation. It shows you the pecking order that governments give to trade and the economy as opposed to the environment. There’s a belief among many that globalization is irresistible. In fact, it’s a product of day-to-day choices by governments.

Has there been anything in the process of globalization that has made you optimistic about transborder cooperation on the environment?

If you look at the efficiency of the European Union in launching the euro, it’s a sign that European governments can work together. If they can pool some of their sovereignty together to achieve economic and monetary ends, there’s hope they and other governments can do the same in the ecological arena. Right now there are about 250 international environmental treaties or conventions, and they suffer from neglect. They’re run by toothless and underfunded secretariats. They’re helpless and hopeless. We’ve got to change attitudes.

- 6496 reads

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.