http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/19/arts/design/19azha.html?adxnnl=1&oref=regi

&adxnnlx=1098155060-Wm9HWrGBV6/043cklut8Aw

New York Times

October 19, 2004

ARCHITECTURE REVIEW | AZHAR PARK

In a Decaying Cairo Quarter, a Vision of Green and Renewal

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

CAIRO - Can thoughtful urban planning heal deep cultural wounds? That is the question raised by the new 74-acre Azhar Park, whose luxurious hilltop gardens are meant to spawn a revival of this city's old decaying Islamic quarter.

Conceived 20 years ago by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, a font of revitalization projects in the Muslim world, the project's aims could not be more noble. The park is the largest green space created in Cairo in over a century, reversing a trend in which unchecked development has virtually eradicated the city's once-famous parks. Built over a mountain of debris that had served as the city's garbage dump for centuries, it also replaces one of Cairo's most trenchant symbols of poverty and decay.

But it is the trust's willingness to engage the harsher realities of the park's surroundings that makes this project unusual. The trust is completing a painstaking restoration of a mile-long segment of the 12th-century Ayyubid wall, which forms the park's western edge. Just beyond it, in the old Islamic quarter known as Darb al-Ahmar, it is working to restore a series of mosques built during the 14th and 15th centuries as well as some Ottoman-era houses. Its development network has also opened a community center whose programs range from reproductive health services to training programs for local craftsmen, many of whom worked on the park's construction.

The result is an urban vision that is startling in its scope. And it reaffirms that the Aga Khan Trust has become one of the most important institutional advocates for architecture in the world. Unlike the Hyatt Foundation's more famous Pritzker Prize, which is essentially a beauty contest, the trust's vast network of programs has long acknowledged that architecture, urban planning, preservation and social and political issues are forever entwined. In so doing, it embraces a more enlightened view of Islamic urban culture.

It is only in its few experiments with contemporary architecture that the project falls short. Cairo has, over the centuries, absorbed a stunning range of cultural influences, from the ancient city in the east to the Europeanized city in the west. The park's architecture could have been an opportunity to bridge that divide. Instead, it expresses a disillusionment with - even an outright distrust of - Western modernity in the Islamic world.

The site, at the city's eastern edge in one of its poorest areas, reflects the planners' social ambitions. For several hundred years, the city's most destitute carted garbage here and then sifted through it for anything of value. The dump gradually grew into a range of hills that extended nearly a mile, burying the old historic wall underneath it. The decaying medieval fabric of the Darb al-Ahmar district is just beyond. To the west of the park is the City of the Dead, a sprawling quarter of ancient tombs and mausoleums that for centuries have been inhabited by the city's poor.

The park, which opened to the public recently, rises out of this context like a virtual Eden. A massive restaurant decorated in a mix of Islamic styles anchors the park's northern end. From here, a series of terraces and gardens - some a mix of flowering trees and bushes, others covered in rolling lawns and date palms - extend to the south, where they culminate in a more modern lakeside restaurant. A long pedestrian spine connects the two ends. Framed by rows of royal palms, it offers a stunning view of the city's ancient Citadel.

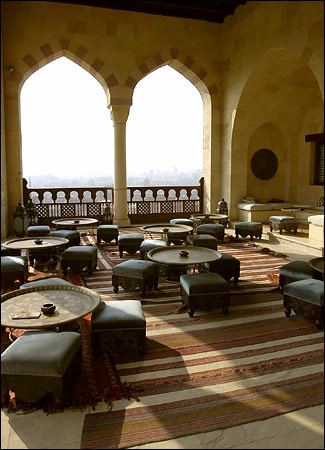

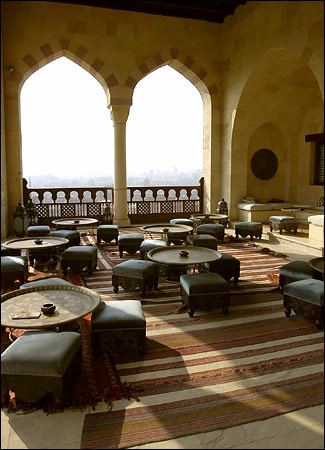

In architectural terms, the park's design echoes the ersatz historical fantasies common to our global culture. The hilltop restaurant is designed around a courtyard with a small traditional fountain at its center. From there, a series of outdoor terraces extend down toward a formal garden. The marble columns are real; much of the stonework was done by hand. Yet the design is an interpretation of Arabic themes: the arched arcades are a mix of Fatimid and Mamluk period styles that would fit comfortably in one of the more luxurious Las Vegas resorts. At the Bellagio, for example, the van Goghs are also real. (The architects, Rami el-Dahan and Soheir Farid, are known for designing resort towns on the Red Sea.)

There is a whiff of artificiality in the lakeside restaurant as well, with its traditional decorative wooden screens and surrounding citrus groves. At times, it even extends into the park itself, where the soporific sounds of piped-in music, from traditional songs to soft rock, mingle with the scents of the aromatic gardens and spectacular displays of floral color. The formula is rooted more in tourism than in local traditions.

But from here, the message becomes more nuanced. A clearing at the top of the park offers a sweeping view of the city below, from the Islamic quarter's minarets to the modern hotels that trace the edge of the Nile River. From there, you slowly descend down a series of paths to the base of the stone Ayyubid wall snaking along the edge of the Islamic quarter.

The area's decrepit housing and labyrinthine streets, once known as a haven for drug dealers, press up against the Ayyubid wall; at various points, their upper stories even rest directly on top of it. Until the project got under way a few years ago, houses tended to collapse under the weight of additional floors and debris - a particularly terrifying outcome of the quarter's remarkable density.

Rather than bulldoze these structures, the trust sought to identify specific points of intervention. One of the wall's ancient gates, for example, leads to a small public square. Framed by the battered facade of the Aslam mosque and littered with carts and furniture, the square will eventually be restored to provide a more welcoming entry to the park. A few blocks away, an Ottoman house has already been transformed into a community center whose upper floor opens directly onto the walkway atop the crenellated wall. Further south, workers can be seen restoring the exterior of the magnificent Khayrbek mosque. To the north, another gate in the wall will soon be transformed into an archaeological visitors' center that will be framed on its park side by an outdoor amphitheater.

The idea is to preserve the ancient neighborhood's character, yet not just in terms of aesthetics: the trust's aim to pinpoint spaces where the community could rebuild itself, and begin to foster a deeper sense of shared identity. In workshops scattered throughout the neighborhood, the trust has trained dozens of local masons, stonecutters and carpenters, many of whom are working on the restoration of the wall.

This strategy is a response, in part, to the tabula rasa form of urban planning so beloved of late Modernists, which sought to solve urban blight by simply bulldozing swaths of old buildings. And it is not particular to the Middle East. A half-century ago, much of the developing world could still embrace Modernist architecture and urban planning as a symbol of progress and prosperity. Today, such schemes are more apt to conjure the West's disregard for local ways of life, and the failures of modernity to deliver on its promise of a more prosperous, humane society.

The trust's approach is to attack urban blight with a kind of surgical precision rather than the brutality of the bulldozer. Its unspoken mission, in essence, is to stem the relentless flow of Western modernity.

But this view of history is narrow. The vibrancy of cities like Cairo or Casablanca, Beirut or Baghdad, sprang from their rich absorption of influences: these are places where cultural frictions between East and West, modernity and tradition, spawned outbursts of remarkable creativity.

Cairo is a particularly cosmopolitan example. Its ancient city is a mix of Coptic churches and Arabic mosques. To the east spreads Ismail Pasha's Europeanized late-19th-century city, whose straight boulevards and English-style gardens - inspired by Haussmann's Paris and now almost all gone - were built to impress foreign dignitaries arriving for the inauguration of the Suez Canal. Nearby are the neo-Classical houses and lush overgrown yards of the Garden City district, an early-20th-century interpretation of Ebenezer Howard's suburban vision for London's outskirts.

These conflicting visions and historical ghosts are what gives the city its magical, dreamlike aura and its humanity.

By presenting an edited version of the past, the Azhar Park project never comes to terms with the tensions - between modernity and tradition, cosmopolitanism and fundamentalism - that simmer beneath the surface of contemporary Islamic culture. And it misses an opportunity to channel them into something more transcendent.

Photos:

Jean-Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

View of the Mohammed Ali mosque, part of the Citadel in Cairo, from the main promenade in the new Azhar Park. The park was built over a centuries-old mountain of debris.

Jean-Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

At the park's edge: part of a restored 12th-century wall and a new community center.

Jean Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

A view of Cairo's new 74-acre Azhar Park, which was built by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, a font of revitalization projects in the Muslim world.

Jean Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

The park is the largest green space created in Cairo in over a century.

Jean Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

The decaying medieval fabric of the Darb al-Ahmar district is just beyond the walls of the park.

Jean Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

The park's trust is also working to restore a series of mosques built during the 14th and 15th centuries.

Jean Claude Aunos/Getty Images, for The New York Times

The upper-level terrace of Azhar Park's hilltop restaurant.