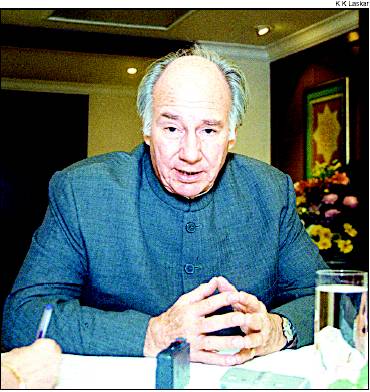

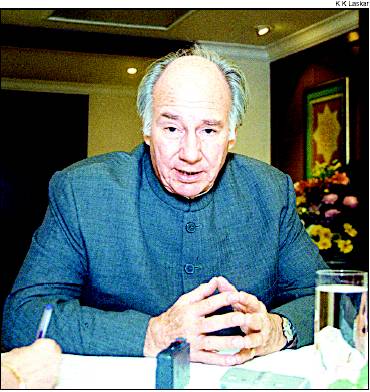

New Delhi: Religious leadership has always been linked with high finance. Uniquely, the institution of the Aga Khan has come to carry the ultimate lifestyle label as well. The triple burden sits lightly on the sharply cut shoulder pads of the present incumbent, revered by his 15 million followers in 25 countries as the 49th direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. Anointed at 20, Prince Karim, now 68, has steered clear of both fundamentalism and the flashy life which killed his father, Prince Aly Khan. Instead, he has crafted an exemplary package which fits equally into sacred or corporate spaces, salon or slum. He is in New Delhi for the 2004 Aga Khan Award for Architecture. This $500,000 triennial prize will be presented this Saturday at Humayun’s Tomb, a site spectacularly restored largely by his foundation.

Isn’t the concept of a ‘spiritual prince’ an anachronism in a secular, democratic age. How have you reinvented the role of the Ismaili Imam?

The Imam’s mandate is to guide and lead as a person of that particular time. The Imam-ship of my grandfather (Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah) was shaped by his colonial times. Mine has been in the context of decolonisation, the break up of the Soviet empire, and now globalisation. We had to create the institutional capacities to deal with a new set of needs — economic and social. The Imam is entrusted with improving quality of life for his followers. He has not only to address issues of faith but those of the real, material world. This dual responsibility is unique to the Imam. The governance of the global community takes place under one constitution, with country-specific rules and regulations.

How have you internalised your two roles as head of both Church and State?

In Shia Islam we don’t differentiate between faith and world. We look at life in its totality, in the context of the individual and the external situation. Forgoing one for the other is contrary to at least our interpretation of Islam.

Would you elaborate on ‘clash of ignorance’, the phrase you prefer to Samuel Huntington’s now-notorious ‘clash of civilisations’?

Today’s world has a new set of opportunities and centrifugal forces in place of the Cold War’s context. But the definition of an educated person hasn’t changed perceptibly since that of the 1960s; the paradigm of education certainly has not kept pace with globalisation. It does not yet provide a comfort level with pluralism. The West’s understanding, its academic context is still Judeo-Christian. It’s apprehensions rise from a lack of knowledge about Islam.

As a man of the world, head of a phenomenal business empire, and brand leader for cultural development, how do you react to your faith being seen as synonymous with terrorism?

I am deeply worried about more than a billion people being tarred by specific historical and regional issues projected as a religious one. Whether you look at the Middle East or Kashmir, there are issues of extreme frustration and despondency. It is unfair to look at hot spots only in relation to Islam. I give you North Ireland, Spain, the Tamil question, the tribal relations in Africa. The Middle East is an inheritance of the first world war. If you leave a problem to — forgive me for using an ugly word — pullulate, decade after decade, it’s certain to end up with deep sickness.

Equally disturbing, most of these conflicts were predictable, and greater focus should have been put on them before they became explosive. The capacity of the international community to assess the degree of future heat isn’t as well defined as it should be.

How have you managed to isolate the Imam-ship, and the Ismailis from the worst stereotypes?

Our source of strength is the importance we place on education, from pre-primary to post graduate. This investment — I prefer the word ‘commitment’ — has taken the community forward. It has been our greatest asset in crisis situations. When you have to leave in a hurry, all you can take with you is your knowledge; and it’s the one resource that helps you resettle faster. This happened in Uganda, Pakistan, Bangladesh.

What is our most precious asset as human beings?

A value system that is both time-resistant and time-adaptable.

And the worst?

Killing, indeed all violence. Going by the record of the last 50 years, this is what offends me most.