http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A36828-2005Jan25.html

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A36828-2005Jan25.htmlWashington Post

26 January 2005

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A36828-2005Jan25.html

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A36828-2005Jan25.html

Washington Post

26 January 2005

By Linda Hales

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, January 26, 2005; Page C01

For nearly 50 years, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV has striven to overcome the celebrity gloss of his life story.

To 20 million Ismaili Muslims in Asia and Africa, the 68-year-old Aga Khan is the 49th hereditary imam, a spiritual leader who traces his lineage directly from the prophet Muhammad.

But to readers of the popular media, he is the billionaire globe-trotting owner of 600 racehorses. When not at his estate outside Paris or at home in Geneva, he presents a tempting target for paparazzi. Their lenses have captured glimpses of him yachting with royalty off the Costa Smeralda resort he developed years ago in Sardinia, basking in the winner's circle with a jockey in his family's emerald racing silks, and squiring a couture-clad Begum Inaara, his estranged second wife, in happier days.

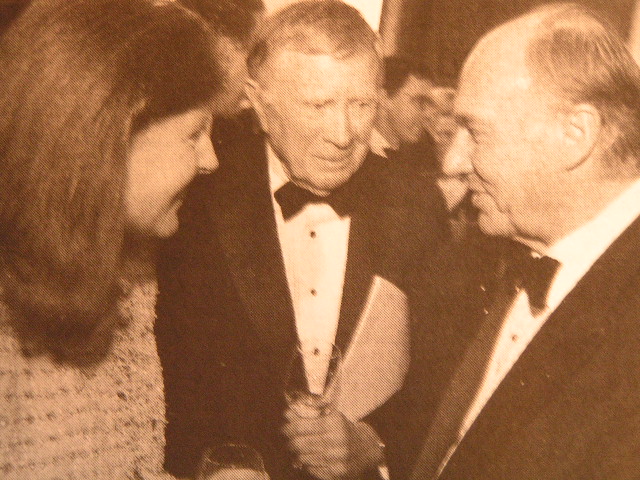

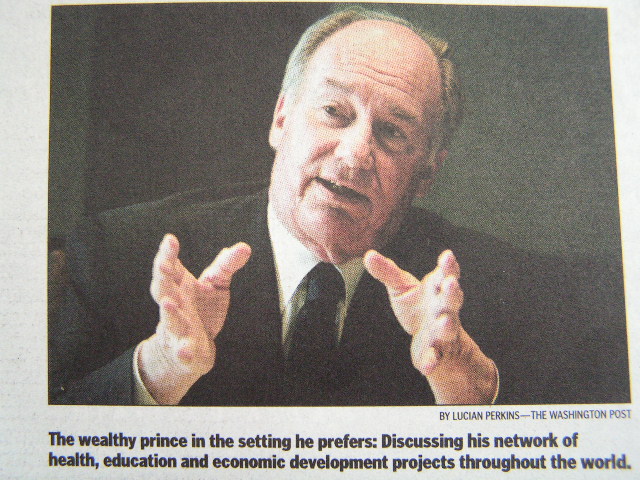

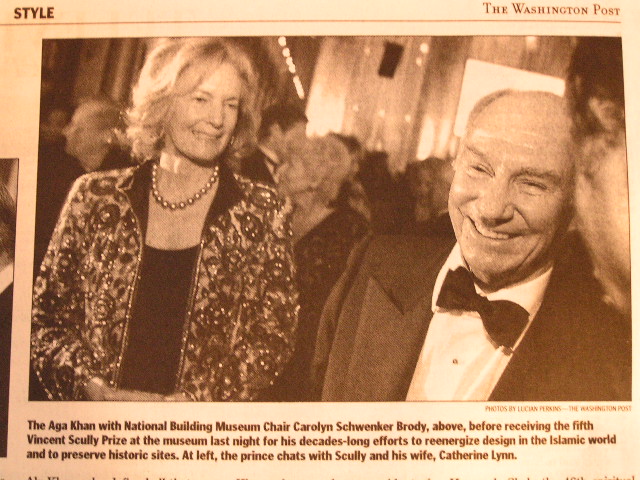

If celebrity follows him, it does not define him. Last night at the National Building Museum, the Aga Khan received the fifth Vincent Scully Prize in recognition of his decades of work to reenergize design in the Islamic world and to preserve historic sites.

His overriding passion is fostering modernity in the Muslim world. Tonight at 6, the Aga Khan will participate in a public program at the museum called "Design in the Islamic World and Its Impact Beyond."

What sort of jet-setter is this?

Behind the Image

"If you want to know who the Aga Khan is, look at what he does," says Hanif Mamdani, an Ismaili Muslim who came here for last night's gala. "That's what's important. That's what occupies his effort and his interests."

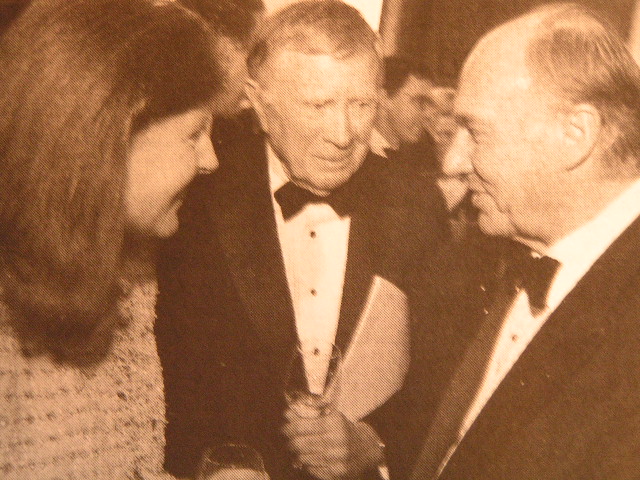

Forbes magazine once described the Aga Khan as "venture capitalist to the Third World." The nerve center is his Aiglemont estate in France. From there, the Aga Khan operates a vast network of health, education and economic development projects, which aides call the world's largest private development agency. The Aga Khan Development Network funds hundreds of rural hospitals and schools, builds factories, luxury hotels and eco-tourism resorts, and develops housing and water and sanitation systems in Asia and Africa.

Forbes magazine once described the Aga Khan as "venture capitalist to the Third World." The nerve center is his Aiglemont estate in France. From there, the Aga Khan operates a vast network of health, education and economic development projects, which aides call the world's largest private development agency. The Aga Khan Development Network funds hundreds of rural hospitals and schools, builds factories, luxury hotels and eco-tourism resorts, and develops housing and water and sanitation systems in Asia and Africa.

Last year, $230 million was spent on 140 projects in 30 countries, according to Amir Kanji, a volunteer affiliated with the network, which extends all the way to the office of FOCUS, a disaster relief agency in Falls Church.

The Aga Khan's people are on the ground in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran, but not in Iraq.

"The network suffers from the vagaries of political strife and crises," Mamdani says.

One of the most expansive projects, 20 years in the making, is the $30 million Al-Azhar Park in Cairo, which is to be dedicated March 25. Ismaili Muslims count Cairo and its Al-Azhar University among their contributions to civilization.

Last night, David M. Schwarz, the founding chairman of the Scully Prize, noted that what the recipients have in common is caring about the world in which they live. The Aga Khan is among those "helping to build a future that may be worthy of our past."

The Aga Kahn will turn 70 in 2007, his 50th year as imam.

"He wants to leave the network behind for his successor," an aide says. "His passion is development. . . . The ultimate ambition is poverty eradication."

To reach out with his modern-is-also-Muslim message, the Aga Khan travels at near supersonic speed. He flew into Washington on an ultra-fast, ultra-long-range Bombardier Global Express, which only begins to purr at Mach .88.

The $30 million Al-Azhar Park in Cairo, 20 years in the making, is one of the Aga Khan's largest urban revitalization projects. It is to be dedicated March 25. (Aga Khan Development Network)

The $30 million Al-Azhar Park in Cairo, 20 years in the making, is one of the Aga Khan's largest urban revitalization projects. It is to be dedicated March 25. (Aga Khan Development Network)

It's not his only plane. There is a transcontinental jet for Europe, a spokeswoman says, another for more distant destinations. And for really remote landings to view projects that his operation is funding, he drops in by helicopter.

Rising Son

The Aga Khan was born in Geneva on Dec. 13, 1936, to Aly Khan and British-born Joan Yarde-Buller. Karim and his younger brother, Amyn, grew up in Nairobi during the war years, then boarded at the exclusive Le Rosey School in Switzerland. He was studying Islamic history at Harvard when, on July 11, 1957, his grandfather's will declared him the 49th imam to the world's far-flung Ismaili sect.

The will passed over his father, Aly Khan, who defined all that was glamorous about pre-World War II Europe: He raced cars and joined the Foreign Legion. He attracted American attention by marrying the film star Rita Hayworth in 1949, after her divorce from Orson Welles. They had a daughter, Yasmin, but by 1953 the marriage had ended. In 1960, he died in an automobile crash in France.

The horse breeding operation's Web site, Agakhanstuds.com, cites the writer Ian Fleming's entry in his personal notebook on Aly Khan's death: "Gamblers just before they die are often given a great golden streak of luck. They get gay and young and rich and then, when they have been sufficiently flattered by the fates, they are struck down."

The Aga Khan seems to be more a man in the image of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, who served as a president of the League of Nations in 1937. His 1954 "Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time," with a foreword by Somerset Maugham, recounts how the Aga Khan was received by Queen Victoria, forged a friendship with Winston Churchill in 1896, befriended King Edward VII and lived through the apex of British imperial might and decline in colonial India.

The Aga Khan seems to be more a man in the image of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, who served as a president of the League of Nations in 1937. His 1954 "Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time," with a foreword by Somerset Maugham, recounts how the Aga Khan was received by Queen Victoria, forged a friendship with Winston Churchill in 1896, befriended King Edward VII and lived through the apex of British imperial might and decline in colonial India.

The Ismaili imams are descended from Muhammad through a cousin and son-in-law, Ali, whose wife Fatima was the prophet's daughter. Over time, Ismailis moved to Syria, Persia and India as well as Africa. Now they reside across the Middle and Near East, especially in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Africa, Europe and North America.

There were two earlier Aga Khans. The title was granted by a king of Persia in the 1830s to Aga Hassanaly Shah, the 46th spiritual leader, or imam, of the Ismaili sect. He moved to India in 1843. The second Aga Khan was named in 1881, but died four years later.

The third Aga Khan, a larger-than-life figure in British colonial India, eventually moved to Britain. In her 1996 book "Throne of Gold: The Lives of the Aga Khans," Anne Edwards describes the 1936 Golden Jubilee of Aga Khan III in Bombay, where tens of thousands of people crowded to see the 220-pound imam presented with his weight in gold. A decade later, Edwards recounts, he received 243 pounds of diamonds, much of which was turned over to investment trusts to benefit Ismailis, who consider themselves an especially prosperous Muslim community.

A Reluctant Celebrity

Even compliments about the Aga Khan are issued anonymously by those who work with him. He declined to be interviewed for this article, but he answered questions at a brief meeting with journalists yesterday afternoon.

One volunteer working on the development network's tsunami relief effort calls the tabloid take on the Aga Khan a "total disconnect" from reality. "You just remain focused," he says. "It is overblown."

The celebrity image is persistent. Bidders on eBay have until Sunday to snap up a January newspaper feature on the Aga Khan's pending divorce, after nearly seven years of marriage, from the German-born Begum, or princess. Gabriele zu Leiningen is a former pop singer turned princess, with a law degree to boot. She gave birth to a son, Aly, in 2000. According to the article on offer, she is said to have threatened, "Give me a £500 million divorce . . . or I'll ask the taxman to probe your finances." Before the ink was dry, a competing tabloid had debunked the story.

The celebrity image is persistent. Bidders on eBay have until Sunday to snap up a January newspaper feature on the Aga Khan's pending divorce, after nearly seven years of marriage, from the German-born Begum, or princess. Gabriele zu Leiningen is a former pop singer turned princess, with a law degree to boot. She gave birth to a son, Aly, in 2000. According to the article on offer, she is said to have threatened, "Give me a £500 million divorce . . . or I'll ask the taxman to probe your finances." Before the ink was dry, a competing tabloid had debunked the story.

The Aga Khan has three children from his first marriage to the British-born Sarah Croker-Poole. After their divorce in 1995, she retained her title as Princess Salimah but sold her jewels at Christie's for $27.7 million.

The Aga Khans are legendary as horse owners, though a spokeswoman plays down the current imam's interest as "the least of his priorities."

According to the Aga Khan Studs Web site, his Aiglemont estate includes "108 boxes, divided into six barns . . . situated in a wonderfully tranquil atmosphere. It is an ideal setting to train horses who perform their daily exercise on gallops that are known by the name 'Les Aigles.' "

From the Web site fans can send an e-postcard from the historic Irish property (1,500 acres) from which his most famous horse, Shergar, was kidnapped in 1983. After winning the English Derby by 10 lengths and the Irish Derby by four, Shergar had been retired to the Aga Khan's stud farm and insured for 10 million pounds. The horse disappeared a year later, rumored to be a victim of the Irish Republican Army. The Web site makes the point that the Aga Khan "refused to blame the many for the misdeeds of the few" and retained his breeding operation in County Kildare.

No official spokesman would hazard a guess at the current Aga Khan's wealth, either personal (the tabloids crow about $1.5 billion) or as a business entity supported by tithes and investments. But one suggested that in light of the wealth amassed by modern tycoons like Bill Gates, there is probably a need to "downsize the myth" about the Aga Khan's holdings.

"Of course, he's not a poor man," the aide says, stressing that "it's what he does with his money" that matters.

Pursuing Diversity

At yesterday's roundtable in the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Washington, the Aga Khan wore banker's gray and spoke in the soft, modulated voice of a diplomat using the arcane vocabulary of international development agencies.

"Civil society is the most urgent single goal," he said. Nuclear war and the spread of HIV-AIDS are his biggest fears. He was adamant about the need for a "pluralistic" society.

As if to discount expectations, and rumors of fabled wealth,

he cautioned that, "In terms of the world's needs, we're a drop in the ocean."

The primary vehicle for his efforts is the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology has educated a generation of architects, planners, teachers and researchers, most from the Islamic world, since 1979. The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, given every three years, is credited with generating a rebirth of Islamic architecture in a skyscraper age. Among last year's recipients was Argentina-born architect Cesar Pelli, whose Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur provide a dynamic example of Islamic aesthetics and 21st-century skyscraper technology.

Tomorrow, after the Aga Khan's rare public appearance here, he'll be off to Ottawa, where Ismaili Muslims who fled Uganda during Idi Amin's regime are establishing what spokesmen describe as a "global center for pluralism."

"A lot of people talk about diversity," says one. "The Aga Khan recognizes that the world is a multifaceted place. He operates with the basic belief that the world is a better place for it."

===================================================================

http://msnbc.msn.com/id/6868603/Highlights from Washington Post

256 January 2006

Updated: 1:08 a.m. ET Jan. 26, 2005

By Linda Hales

- For nearly 50 years, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV has striven to overcome the celebrity gloss of his life story.

To 20 million Ismaili Muslims in Asia and Africa, the 68-year-old Aga Khan is the 49th hereditary imam, a spiritual leader who traces his lineage directly from the prophet Muhammad.

But to readers of the popular media, he is the billionaire globe-trotting owner of 600 racehorses. When not at his estate outside Paris or at home in Geneva, he presents a tempting target for paparazzi. Their lenses have captured glimpses of him yachting with royalty off the Costa Smeralda resort he developed years ago in Sardinia, basking in the winner's circle with a jockey in his family's emerald racing silks, and squiring a couture-clad Begum Inaara, his estranged second wife, in happier days.

If celebrity follows him, it does not define him. Last night at the National Building Museum, the Aga Khan received the fifth Vincent Scully Prize in recognition of his decades of work to reenergize design in the Islamic world and to preserve historic sites.

His overriding passion is fostering modernity in the Muslim world. Tonight at 6, the Aga Khan will participate in a public program at the museum called "Design in the Islamic World and Its Impact Beyond."

What sort of jet-setter is this?

Behind the image

"If you want to know who the Aga Khan is, look at what he does," says Hanif Mamdani, an Ismaili Muslim who came here for last night's gala. "That's what's important. That's what occupies his effort and his interests."

Forbes magazine once described the Aga Khan as "venture capitalist to the Third World." The nerve center is his Aiglemont estate in France. From there, the Aga Khan operates a vast network of health, education and economic development projects, which aides call the world's largest private development agency. The Aga Khan Development Network funds hundreds of rural hospitals and schools, builds factories, luxury hotels and eco-tourism resorts, and develops housing and water and sanitation systems in Asia and Africa.

Last year, $230 million was spent on 140 projects in 30 countries, according to Amir Kanji, a volunteer affiliated with the network, which extends all the way to the office of FOCUS, a disaster relief agency in Falls Church.

The Aga Khan's people are on the ground in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran, but not in Iraq.

"The network suffers from the vagaries of political strife and crises," Mamdani says.

One of the most expansive projects, 20 years in the making, is the $30 million Al-Azhar Park in Cairo, which is to be dedicated March 25. Ismaili Muslims count Cairo and its Al-Azhar University among their contributions to civilization.

Last night, David M. Schwarz, the founding chairman of the Scully Prize, noted that what the recipients have in common is caring about the world in which they live. The Aga Khan is among those "helping to build a future that may be worthy of our past."

The Aga Kahn will turn 70 in 2007, his 50th year as imam.

"He wants to leave the network behind for his successor," an aide says. "His passion is development. . . . The ultimate ambition is poverty eradication."

To reach out with his modern-is-also-Muslim message, the Aga Khan travels at near supersonic speed. He flew into Washington on an ultra-fast, ultra-long-range Bombardier Global Express, which only begins to purr at Mach .88.

It's not his only plane. There is a transcontinental jet for Europe, a spokeswoman says, another for more distant destinations. And for really remote landings to view projects that his operation is funding, he drops in by helicopter.

Rising son

The Aga Khan was born in Geneva on Dec. 13, 1936, to Aly Khan and British-born Joan Yarde-Buller. Karim and his younger brother, Amyn, grew up in Nairobi during the war years, then boarded at the exclusive Le Rosey School in Switzerland. He was studying Islamic history at Harvard when, on July 11, 1957, his grandfather's will declared him the 49th imam to the world's far-flung Ismaili sect.

The will passed over his father, Aly Khan, who defined all that was glamorous about pre-World War II Europe: He raced cars and joined the Foreign Legion. He attracted American attention by marrying the film star Rita Hayworth in 1949, after her divorce from Orson Welles. They had a daughter, Yasmin, but by 1953 the marriage had ended. In 1960, he died in an automobile crash in France.

The horse breeding operation's Web site, Agakhanstuds.com, cites the writer Ian Fleming's entry in his personal notebook on Aly Khan's death: "Gamblers just before they die are often given a great golden streak of luck. They get gay and young and rich and then, when they have been sufficiently flattered by the fates, they are struck down."

The Aga Khan seems to be more a man in the image of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, who served as a president of the League of Nations in 1937. His 1954 "Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time," with a foreword by Somerset Maugham, recounts how the Aga Khan was received by Queen Victoria, forged a friendship with Winston Churchill in 1896, befriended King Edward VII and lived through the apex of British imperial might and decline in colonial India.

The Ismaili imams are descended from Muhammad through a cousin and son-in-law, Ali, whose wife Fatima was the prophet's daughter. Over time, Ismailis moved to Syria, Persia and India as well as Africa. Now they reside across the Middle and Near East, especially in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Africa, Europe and North America.

There were two earlier Aga Khans. The title was granted by a king of Persia in the 1830s to Aga Hassanaly Shah, the 46th spiritual leader, or imam, of the Ismaili sect. He moved to India in 1843. The second Aga Khan was named in 1881, but died four years later.

The third Aga Khan, a larger-than-life figure in British colonial India, eventually moved to Britain. In her 1996 book "Throne of Gold: The Lives of the Aga Khans," Anne Edwards describes the 1936 Golden Jubilee of Aga Khan III in Bombay, where tens of thousands of people crowded to see the 220-pound imam presented with his weight in gold. A decade later, Edwards recounts, he received 243 pounds of diamonds, much of which was turned over to investment trusts to benefit Ismailis, who consider themselves an especially prosperous Muslim community.

A reluctant celebrity

Even compliments about the Aga Khan are issued anonymously by those who work with him. He declined to be interviewed for this article, but he answered questions at a brief meeting with journalists yesterday afternoon.

One volunteer working on the development network's tsunami relief effort calls the tabloid take on the Aga Khan a "total disconnect" from reality. "You just remain focused," he says. "It is overblown."

The celebrity image is persistent. Bidders on eBay have until Sunday to snap up a January newspaper feature on the Aga Khan's pending divorce, after nearly seven years of marriage, from the German-born Begum, or princess. Gabriele zu Leiningen is a former pop singer turned princess, with a law degree to boot. She gave birth to a son, Aly, in 2000. According to the article on offer, she is said to have threatened, "Give me a £500 million divorce . . . or I'll ask the taxman to probe your finances." Before the ink was dry, a competing tabloid had debunked the story.

The Aga Khan has three children from his first marriage to the British-born Sarah Croker-Poole. After their divorce in 1995, she retained her title as Princess Salimah but sold her jewels at Christie's for $27.7 million.

The Aga Khans are legendary as horse owners, though a spokeswoman plays down the current imam's interest as "the least of his priorities."

According to the Aga Khan Studs Web site, his Aiglemont estate includes "108 boxes, divided into six barns . . . situated in a wonderfully tranquil atmosphere. It is an ideal setting to train horses who perform their daily exercise on gallops that are known by the name 'Les Aigles.' "

From the Web site fans can send an e-postcard from the historic Irish property (1,500 acres) from which his most famous horse, Shergar, was kidnapped in 1983. After winning the English Derby by 10 lengths and the Irish Derby by four, Shergar had been retired to the Aga Khan's stud farm and insured for 10 million pounds. The horse disappeared a year later, rumored to be a victim of the Irish Republican Army. The Web site makes the point that the Aga Khan "refused to blame the many for the misdeeds of the few" and retained his breeding operation in County Kildare.

No official spokesman would hazard a guess at the current Aga Khan's wealth, either personal (the tabloids crow about $1.5 billion) or as a business entity supported by tithes and investments. But one suggested that in light of the wealth amassed by modern tycoons like Bill Gates, there is probably a need to "downsize the myth" about the Aga Khan's holdings.

"Of course, he's not a poor man," the aide says, stressing that "it's what he does with his money" that matters.

Pursuing diversity

At yesterday's roundtable in the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Washington, the Aga Khan wore banker's gray and spoke in the soft, modulated voice of a diplomat using the arcane vocabulary of international development agencies. "Civil society is the most urgent single goal," he said. Nuclear war and the spread of HIV-AIDS are his biggest fears. He was adamant about the need for a "pluralistic" society.

As if to discount expectations, and rumors of fabled wealth, he cautioned that, "In terms of the world's needs, we're a drop in the ocean."

The primary vehicle for his efforts is the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology has educated a generation of architects, planners, teachers and researchers, most from the Islamic world, since 1979. The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, given every three years, is credited with generating a rebirth of Islamic architecture in a skyscraper age. Among last year's recipients was Argentina-born architect Cesar Pelli, whose Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur provide a dynamic example of Islamic aesthetics and 21st-century skyscraper technology.

Tomorrow, after the Aga Khan's rare public appearance here, he'll be off to Ottawa, where Ismaili Muslims who fled Uganda during Idi Amin's regime are establishing what spokesmen describe as a "global center for pluralism."

"A lot of people talk about diversity," says one. "The Aga Khan recognizes that the world is a multifaceted place. He operates with the basic belief that the world is a better place for it."

© 2005 The Washington Post Company