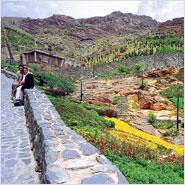

In a country where seven out of every ten inhabitants are under 30 years of age, Bagh-e Ferdowsi is significant in far more than name. Along with providing a temporary refuge from Tehran's concrete sprawl and car-strangled streets, the park has become a haven for young people--especially couples--to meet, stroll, and even walk hand in hand without fear of being harassed or arrested by city or religious police. Some more daring women remove their chadors in defiance of Islamic law.

Bagh-e Ferdowsi was one of nine projects selected for the award in 2001. In its report the jury lauded park designers Gholamreza Pasban Hazrat and Fathali Farhad Abozzia for their "innovative approach to environmental design" and for promoting an "awareness of conservation and nature amongst the urban population of Tehran." The report made no mention of the subversive use Tehran's young people made of their city's largest open space, but that function was certainly noticed by the jury.

"The Aga Khan Award often goes to spaces with humanitarian connotations," says Diba, a member of the 2001 jury. "These are spaces of freedom, dialogue, gathering. They are almost always antidogmatic, and very often antigovernment. In many ways Bagh-e Ferdowsi is like Tehran with its twelve million people: simply too big for the government to control."

While some cultural officials in Iran try to reintroduce elements of Persian history--and of Iran's recent secular past--into their country's Islamic society, their neighbor Turkey is trying to reestablish elements of its Islamic past in the state's secular framework. Born in 1923 out of the vestiges of the Ottoman Empire after its collapse following World War I, the modern state of Turkey literally rescripted itself--redrafting its borders, shifting from Islamic to secular society and from autocratic to democratic government, even converting its alphabet from Arabic to Roman characters.

The selections of the Aga Khan Award in Turkey do not in themselves foster historical reconciliation. But as in Iran, the winning projects chart a decisive arc in the evolution of contemporary Turkey. The Turkish Historical Society, which won the award in 1980, is housed in a contemporary building that incorporates many traditional Ottoman elements. Its three-story central atrium is a direct reference to the Ottoman madrasa, a welcome departure from Ankara's dominant International Style. Another 1980 winner, Ertegün House, is a 100-year-old home located on the site of ancient Halicarnassus that was transformed into a summer residence in 1973.

Both the Turkish Historical Society and the Ertegün House are the work of architect Turgut Cansever, who won a third Aga Khan Award in 1992 with Demir Holiday Village, north of Bodrum. A development of 42 vacation homes set in a shaded wood on Mandalya Bay, the village has drawn accolades as an example of environmentally and socially responsible development. The 1992 jury also singled out the Palace Parks Program in Istanbul for recognition. Involving the conversion of Ottoman palaces and pavilions into public spaces and parks, the project is a useful exploitation of resources and, on a social level, a successful rehabilitation of a part of Turkey's Ottoman past.

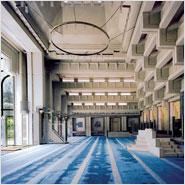

While Turkey seems willing--and even enthusiastic--to reexamine its discredited Ottoman past, there is significant resistance regarding the country's Islamic heritage. Both Islamists and secularists contested the contemporary mosque that architects Behruz and Can Cinici designed for the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara in 1989. Built largely in reinforced concrete, the rectangular prayer hall won the Aga Khan Award in 1995. Secularists protested the introduction of any religious structure into the National Assembly campus. Traditionalists groused over the lack of traditional elements in Cinici's design: the customary minaret tower is represented by a cypress tree planted above a series of balconies. Instead of facing a traditional opaque mihrab, worshippers at the mosque address their prayers and meditations toward a glass niche that opens onto a cascading sunken garden.

"Pure order and geometry is very important to be close to God," says 70-year-old Behruz Cinici, who threatened to resign during the project rather than trace a traditional minaret. "This is a building of faith, but commissioned and built by a secular state. And its essence describes liberty, democracy, and equality, all the aspects on which our state is built."

For Cinici the mosque's design represents the original essence of Islam, emanating from the mosques built in Medina and Damascus when the faith was still young. The rectilinear design, soft natural lighting, and humble materials of the Grand National Assembly mosque create an atmosphere of contemplation. It is a space of transition--of the sacred and secular--and as in so many projects recognized by the Aga Khan Award, one of individual and collective freedom. "This building isn't about an official religion of state," Cinici says. "It's about a belief system. Islam is above all about the individual. In true Islam, there is no need for any figure or institution between human being and God."

PAGE 3| BACK TO FIRST